TONY LOPEZ: The Field

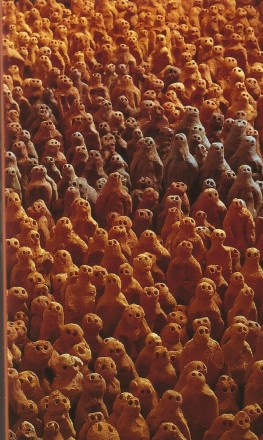

Antony Gormley, Field for the British Isles (detail) from the book cover Other: British and Irish Poetry since 1970, Wesleyan University Press, 1999

It was on a Saturday morning three or four weeks ago that Sara and I drove to Ilminster near Yeovil in South Somerset for the opening reception of Antony Gormley’s Field for the British Isles installation at Barrington Court, a National Trust house.

From here we take the back roads through beech woods and over Woodbury Common towards Ottery, joining the noisy concrete A30 near Exeter airport. This is where Swampy and his fellow protestors were camped out in the trees and dug into tunnels to delay the building of the new road. Once you get up beyond Honiton and continue on the A303 it’s an alternative route to London, slower but more direct; I like the long green tunnels as the road gets into the Blackdown hills, passing signs for Combe Raleigh, Upottery, and Buckland St Mary. It was just spotting with rain when we drove slowly through Barrington, obviously an estate village, following signs to the great house.

This was an invitation that came through the Arts Council because I am a member of their Southwest Regional Council, a voluntary job that is roughly equivalent to a non-executive board member or a school governor. I go to perhaps ten meetings a year. The invitation was a welcome one: I like Antony Gormley’s work very much indeed and the Field is a piece that I’ve long wanted to see for real. I’ve seen it many times in photographs and could imagine what the whole thing might look like but with sculpture, if it’s any good, the physical presence is something else again. You can’t predict just what kind of impact the work will have in its own space.

Gormley’s Field for the British Isles has a massive and quite particular presence unlike other works by him that are for good reason also very widely known. The work is a multitude of clay figures, quite simply made, that look back at the viewer from where they are assembled as a crowd. It is a work that communicates, like no other I have come across, the idea of the many rather than the few. It is a pure sculpture, making physical certain ideas and communicating very effectively in terms of form and space. I suppose that one very remarkable aspect of Gormley’s work as a whole is the way that he employs the human figure and renews representational sculpture which had, before he came to prominence, seemed to be mostly played out. That sense of being at the end of a long tradition, the condition we call belatedness, is crucially important, as is the ability to communicate more widely, beyond the art specialists.

So what we see is a crowd of fairly similar, basic, but recognisably human figures made of the same terracotta clay used for ordinary building bricks or tiles. There are 40,000 of them, hand made to the same rough dimensions but each one different in height and shape, showing variation also in colour, size of head, precise position of the eyes, and we see them grouped in height and colour so that the form of the packed room undulates like the swell of the sea or waves in a field of barley.

Looking at the variety of individual figures, each with their simple pressed-out eyes facing the viewer, you can’t fail to think of our crowded life in cities, of the mass of humanity at festivals and religious assemblies, the pressure that we all put on the planet’s resources. The sculpture locates meaning in this multitude, proposes that there is much that connects us, whilst recognising the individuality of those who make up the crowd. This is the opposite of the heroic individual figure that is so influential and in fact works as the underlying assumption or ideology in our culture. What we call Romanticism, the cult of individual sensibility, creativity, genius, and self-expression, is what is absent in this crowd-focused work. Instead of depicting an heroic individual and expressing identity and skill in carving or modelling an artwork that communicates an individual vision, Gormley has abdicated that implied aristocratic or elite narrative.

Don’t get me wrong: Gormley’s fame as an artist gives him a privileged position to make large-scale interventions in the British urban and rural landscape. Turner prize winning Gormley, OBE, plc, is an international brand. However, his Field for the British Isles is fundamentally democratic and focused on the crowd.

I can’t remember when I first saw a photo and heard of this work, probably some time in the early nineties in a Sunday newspaper supplement. I do remember my friend Richard Caddel’s excitement about it when he was finishing the anthology Other: British and Irish Poetry since 1970 (1999) that he edited with Peter Quartermain for Wesleyan University Press – no accident that it was published in the USA. Ric had secured permission to use Gormley’s Field for the British Isles as the cover and was absolutely delighted. Nothing could be better to provide an image for the poetry that had been crowded out of the UK record by the main British publishers’ inbred few. I think they were called the ‘new generation’ at that time.

I’m attracted to visual work that uses grids and non-identical repetition, like abstract patterned quilts, and painting and drawing that sets up an optical field. When The Figures published my False Memory (also in USA) in 1996, Geoffrey Young’s cover design was based on Charles Le Dray’s Milk and Honey, 1994-96, a sculpture that had just been purchased for the collection at the Whitney Museum of American Art. This piece is a glass shelving cabinet holding thousands of miniature porcelain pots, and each one is different: tiny vases, bowls, jugs, bottles, pots and cups. The work has a kind of manic obsessive quality and shows amazing patience and skill. I had not seen Le Dray’s work before Geoff sent me a slide and I couldn’t have imagined a better cover design. The use of craft rather than high art techniques and the fine-detailed obsessive precision is typical of Charles Le Dray who also often works with textiles and embroidery. Another favourite piece by him is a child-sized shiny embroidered jacket entitled World’s Greatest Dad.

So the work Field for the British Isles already has a back-story for me, I associate it with the memory of my late friend, poet, publisher and editor Ric Caddel. It’s also bound up with the incomplete and temporary sense of community articulated by the publication Other. The decentred aesthetic of the series and the grid is important. But the Field has its own powerful presence that comes first of all from the way that it was made.

People of all ages from St Helens in Merseyside were recruited as volunteers to make the tens of thousands of little clay figures. Working in a school hall, they were each given a quantity of prepared clay to measure out into pieces by weight and were shown how to make the figures and put in the eyes by pressing a pencil into the clay. They were encouraged to form their own figures, not to copy an exact pattern, and so the variation was built into the design. The figures were fired at a brickworks and the work was installed for the first time at Tate Liverpool in 1993. It was acquired for the Arts Council collection in 1995 with the assistance of the Art Fund and The Henry Moore Foundation. It has been exhibited on loan about once a year since then and each installation requires a new team of voluntary installers to be trained and to work on site for more than a week. The agreement for installation stipulates that the volunteers be given hot meals whilst they are working on the project. This community aspect of the work is built into the concept and the physical making and into each installation.

The logic of the Arts Council working together with the National Trust certainly makes sense. If only the access to National Trust properties were not so expensive and thus out of reach for so many people. If you don’t drive you’d never get to most of them. It’s not surprising in England that crowds will pay a hefty entrance fee to see aristocrats’ home furnishings and thus reproduce radical inequality as a leisure theme. I understand that the audience for contemporary art and for stately homes probably doesn’t overlap much in England. So putting modern art into stately homes means that National Trust visitors and members get to see art they wouldn’t normally see. I wonder how many people in the art audience would go to stately homes that they wouldn’t normally visit outside of this scheme? I would be unlikely to take the time to drive to Barrington Court to see the house. It is a fine Tudor house with wonderful gardens conceived as separate rooms inspired by Gertrude Jekyll, but I’m not sure I’d have driven three hours round trip to see it without the prospect of the Antony Gormley work on show. If I was a National Trust member looking to make the best use of my annual membership I would probably have got round to it. I’ve seen most of the houses further west.

Barrington Court is unusual in that the main house isn’t furnished at all. The whole place is empty with no carpets no furniture and no pictures except for a few photos of the Lyle family, the sugar people, who are previous tenants. These are just family snapshots of rich people, and no trade more clearly signifies the origins of our great houses in slavery and colonial power. The installation of the Field for the British Isles is a really useful addition to enliven the empty house. It is installed in three large ground floor rooms and the figures fill up all of the space, so the viewer must stand at the doorway and look in, or rather queue to get to the doorway. The silent clay figures look back at viewer and the work takes on the meanings already assembled in the fabric of the house.

In a gallery you might use a half or two thirds of a very big room, leaving space to get your viewers in and out, hopefully through different doors. This show requires more than three invigilators who spend their time in a corridor; like the installers, they would be National Trust volunteers. You see across the room from one corner, and inside there are details like wooden panelling, window bays, bookcases, fireplaces and staircases that the figures crowd up against. There is a darker patch of figures that stands out by the fireplace; the light from the windows has a different effect at different times of day. You wouldn’t see the work like this in a white-walled gallery.

In the marquee on the South Lawn we listened to speeches about the National Trust and the Arts Council working together to put contemporary art into historic houses, we heard about the community spirit of the volunteer installers. There were guests from arts organisations all over the region. We met the National Trust managers of the house who were hosting the party. There was contemporary folk music in the marquee while we queued for the excellent buffet lunch. On the way back to the car we looked at the Rose and Iris Garden, the White Garden, the Lily Garden, the Kitchen Garden and the Arboretum. We visited the craft workshops and bought some pottery. Contemporary art is the story that gets gathered up into a weekend jaunt, a chance to take some time off. The National Trust has the real estate, if only we could get the transport and general access sorted.

Copyright Tony Lopez 26 May 2012

Tony Lopez is an English poet of international repute. His latest books are Only More So and a new edition of False Memory, both published by Shearsman in 2012. http://www.shearsman.com/pages/books/authors/lopezTA.html

He was born in Stockwell in 1950 and grew up in Brixton, South London. He began work by writing fiction for newspapers and magazines, and published five crime and science fiction novels before going to university at Essex and then Cambridge. He has received awards from the Wingate Foundation, the Society of Authors, the Arts and Humanities Research Council, and Arts Council England. His poetry is featured in The Art of the Sonnet (Harvard University Press), Twentieth-Century British and Irish Poetry (Oxford University Press), Vanishing Points: New Modernist Poems (Salt), The Reality Street Book of Sonnets (Reality Street), Other: British and Irish Poetry since 1970 (Wesleyan University Press), and Conductors of Chaos (Picador). His critical writings are collected in Meaning Performance: Essays on Poetry (Salt) and The Poetry of W.S. Graham (Edinburgh University Press). He taught for many years at the University of Plymouth, where he was appointed the first Professor of Poetry; he now works on public art incorporating text. He is married with two grown up children and lives in Exmouth in Devon. http://www.tonylopez.org.uk/

LEAVE A COMMENT

From the Junction Box

- Contributors and Links to Pages 1- 4

- Editorial to Issue 17: The John James / Chris Torrance Special

- Gavin Selerie: Marks Outside the Spa

- Elisabeth Bletsoe: Two Poems and a Miscellany for Chris Torrance

- Allen Fisher: Leeks and Leaves for Chris Torrance

- Ian Brinton: Notes from a Correspondence with Chris Torrance

- Elaine Randell: Chris, Barry and Me

- Ian Davidson: Tripping

- Peter Finch: Torrance

- Tilla Brading: Pieces for Chris Torrance