KELVIN CORCORAN: Wordy Postcard 1

By chance I’d been in Athens when the downgrading of Greek credit worthiness began. I was talking to an Athenian lawyer. Her view then was that, yes it would be hard for people on fixed incomes. Professionals, like lawyers, would just charge more for their services; this wasn’t said dismissively but I wonder if she still holds this plain view of present events. It feels like an older, harder pattern has returned. The series of articles in London Review of Books by John Lanchester seems to be accurate about the economics of the crisis. The young are leaving. I’m told Australia is actively recruiting for new Australians. The surface style of mainstream European expectations is being effaced. Driving across the Peloponnese is instructive. The big, new post-Olympic Games roads are empty. Some of the towns we drove through looked like a war had rolled by and just stopped from exhaustion. Friends tell me the health system has become an emergency only service, unemployment and homelessness have rocketed and attacks upon immigrants in Athens are up markedly.

Late one night we heard rembetika, the Levantine blues, sneaking out of a narrow street. For drinks, two young men and an older man were performing outside a kafaneio. The old man was missing several fingers, a typical injury for fishermen who dynamite the fish to make catching them easier. The music was completely authentic, the sardonic growl of the singing, its bite, its pissed offness and weary companionship. The young men and the old man all knew the same songs. It was like we’d slipped back decades to earlier bad times; the population exchange in 1923, the war, the civil war. That the crisis is good for rembetika is no comfort to the newly poor. The bloody minded singing, its mode of bitterness tells you about this dark continuity.

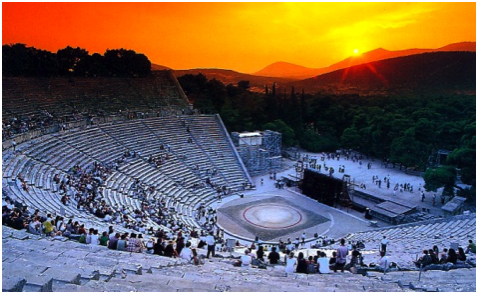

Such continuity is deeper than I at first thought. We went late one night to a performance in the ancient amphitheatre at Epidaurus. The play was Heracles by Euripides. I’d been to the site before but had not seen a performance. The performance is in Modern Greek. I read the play in English several times and checked in with my friend Maria during the performance – and now this part Kelvin is when, and Madness is saying. And indeed, as the guidebooks say, the acoustics are astonishing. From the centre spot of the circular orchestra you can hear the merest whisper to the top of the 54 tiers of seating and, perhaps, spreading out over the Argolid hills; the original psychorama to the plays themselves. The theatre has been there since the 4th century BC. The original capacity was 15,000. I think there were approximately 10,000 of us there that night.

As ever the drama begins before the play itself, friends greeting one another, the selecting and settling of your part of the stone bench. Celebrities arrived in their down front posh stone benches, cushion provided, and a few were greeted with applause. The reception suggested these individuals were perhaps soap opera actors rather than politicians. The sky darkened, the play began and we became near silent. Heracles returns from his labours, releases his wife and children from captivity by the usurper Lycus. All’s well. And then Heracles is made mad and slaughters his family – and by now it is very dark. Aside from succumbing to the unwearied grip of the tragedy several moments in the play brought us back to present conditions. One in particular was well received. Amphitryon, father of Heracles, updates Heracles on the situation in Thebes. (This is the Vellacott translation.)

There’s a large class of needy men, who make a show

Of being prosperous; Lycus has their strong support.

They raised the riots; they sold Thebes to slavery

In hope of lawless plunder, to redeem their own

Bankruptcy, caused by extravagance and idleness.

But the play is two and a half thousand years old, removed from us by translation and cultural specifics, and besides everything is different now.

Kelvin Corcoran’s first book was Robin Hood in the Dark Ages in1985. Nine subsequent collections have been enthusiastically received and his work has been anthologised in the UK and USA. The sequence Helen Mania was made a Poetry Book Society choice. Kelvin Corcoran has read at various art galleries in the UK in response to the Arts Council touring exhibitions, Spotlight on St. Ives and Geometry of Fear. His New and Selected Poems is now available from Shearsman Books along with two major collections Backward Turning Sea (2008) and Hotel Shadow (2010). Words Through A Hole Where Once There Was A Chimpanzee’s Face is now available from Longbarrow Press. Work with the musicians of Tria Kalistos in the recording and performance of several longer poems continues.

LEAVE A COMMENT

From the Junction Box

- Contributors and Links to Pages 1- 4

- Editorial to Issue 17: The John James / Chris Torrance Special

- Gavin Selerie: Marks Outside the Spa

- Elisabeth Bletsoe: Two Poems and a Miscellany for Chris Torrance

- Allen Fisher: Leeks and Leaves for Chris Torrance

- Ian Brinton: Notes from a Correspondence with Chris Torrance

- Elaine Randell: Chris, Barry and Me

- Ian Davidson: Tripping

- Peter Finch: Torrance

- Tilla Brading: Pieces for Chris Torrance